One of the worst things a teacher can say to a student is, “Sorry, but you’ll just have to memorize it”.

Memorization is not how we acquire knowledge.

Memorization leads to language learners uttering sentences such as, “I have fly-flew-flown to Italy twice in my life.”

I blame the irregular verb list for this. It is not intended for students!

This discussion is a long one, but I think you’ll find it valuable. I will outline some of the problems with using lists as language learning material and give a very long solution which is in the form of a lesson plan. As you probably know, writing a lesson plan for another person isn’t easy because… well, you aren’t in my head! If any of my instructions or anything else is unclear, or I’ve assumed something that isn’t obvious to you, please don’t hesitate to make a comment asking me to clarify myself.

Every language student I’ve ever met has a list of irregular verbs. You’ve seen these old scraps of paper. Most have been photocopied, aslant, no doubt, from the appendix of some long-forgotten grammar book, are folded multiple times, and have coffee stains Some probably include archaic items such as smite-smote-smitten, although being so far down the list, (in the ‘S’ section), that most students probably haven’t even got that far, not even after toting the damnable paper around for five years.

Has this sheet of paper, held onto for years, done the learner any good? Can they use the simple past or past participle forms automatically or do they stop mid-way through a sentence to mentally or often audibly recite the paradigm before hitting on the correct form as illustrated above?

This irregular verb list is a handy abbreviated resource for teachers ONLY. The standard irregular verb list itself has absolutely no bearing on language whatsoever and serves only to confuse language learners. The information on the list is important to students but just not in that format.

Reference materials, such as dictionaries and grammar reference lists, do not show regular forms such as third person ‘s’, simple past ‘ed’, and present participle -ing. The intended user is assumed to know those forms. As a teacher (the intended user), your job is to explain and expand on the reference materials not to hand them out and expect that the learners can make heads or tails out of them.

That’s the problem. Now for the solution. How do we teach students irregular verb forms in a productive way?

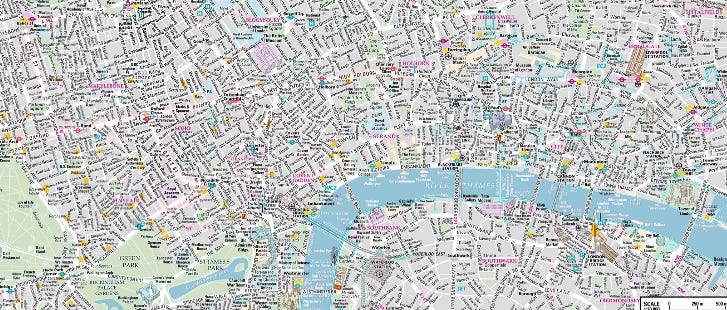

Our aim is to teach irregular verb forms. If we simply give the list without any context, it’s like trying to use a map zoomed in maximally. There are no landmarks. Finding Exeter Street in London is impossible with this map.

The map view above is like teaching fly-flew-flown. We have nothing to direct us. The scope is too small.

Equally important is to limit the information presented to the essentials, unlike this overly detailed map view of the same area. Finding Exeter Street becomes a finding Waldo game!

The map view above is like teaching all the possible information connected to irregular verbs, the history of the Saxons, the etymology, every meaning (many of the irregular verbs have more than ten meanings), etc. Our scope becomes too big for the task.

Neither of those perspectives will help you find Exeter Street. We need some essential context without a lot of unnecessary details.

The map above is basic while retaining the essential details for the task of finding Exeter Street. In short, it has the right perspective.

We can teach irregular verb forms this way. Expand the list into basic sentences, and show the essential landmarks. Nothing more, nothing less.

Let’s start.

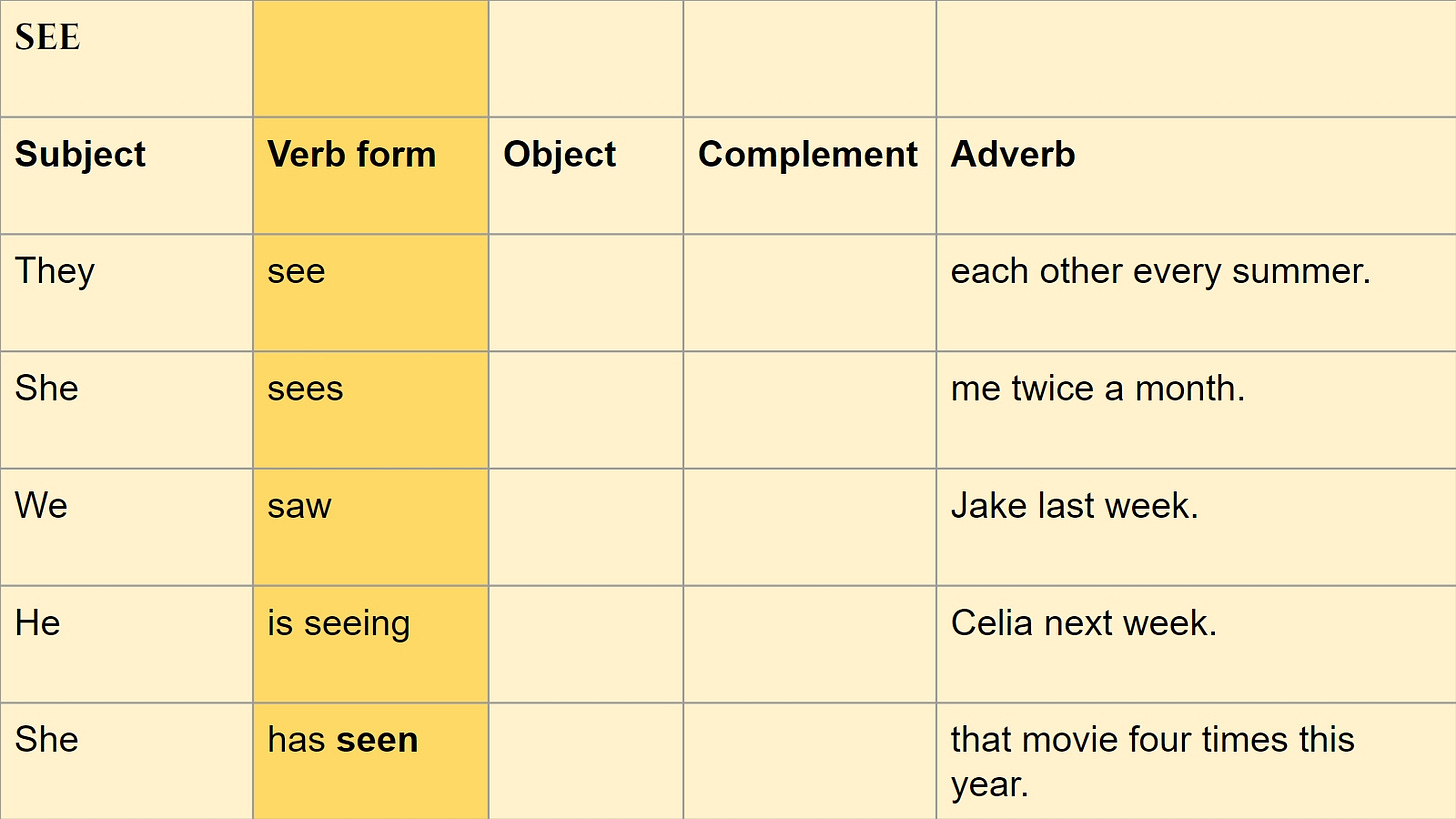

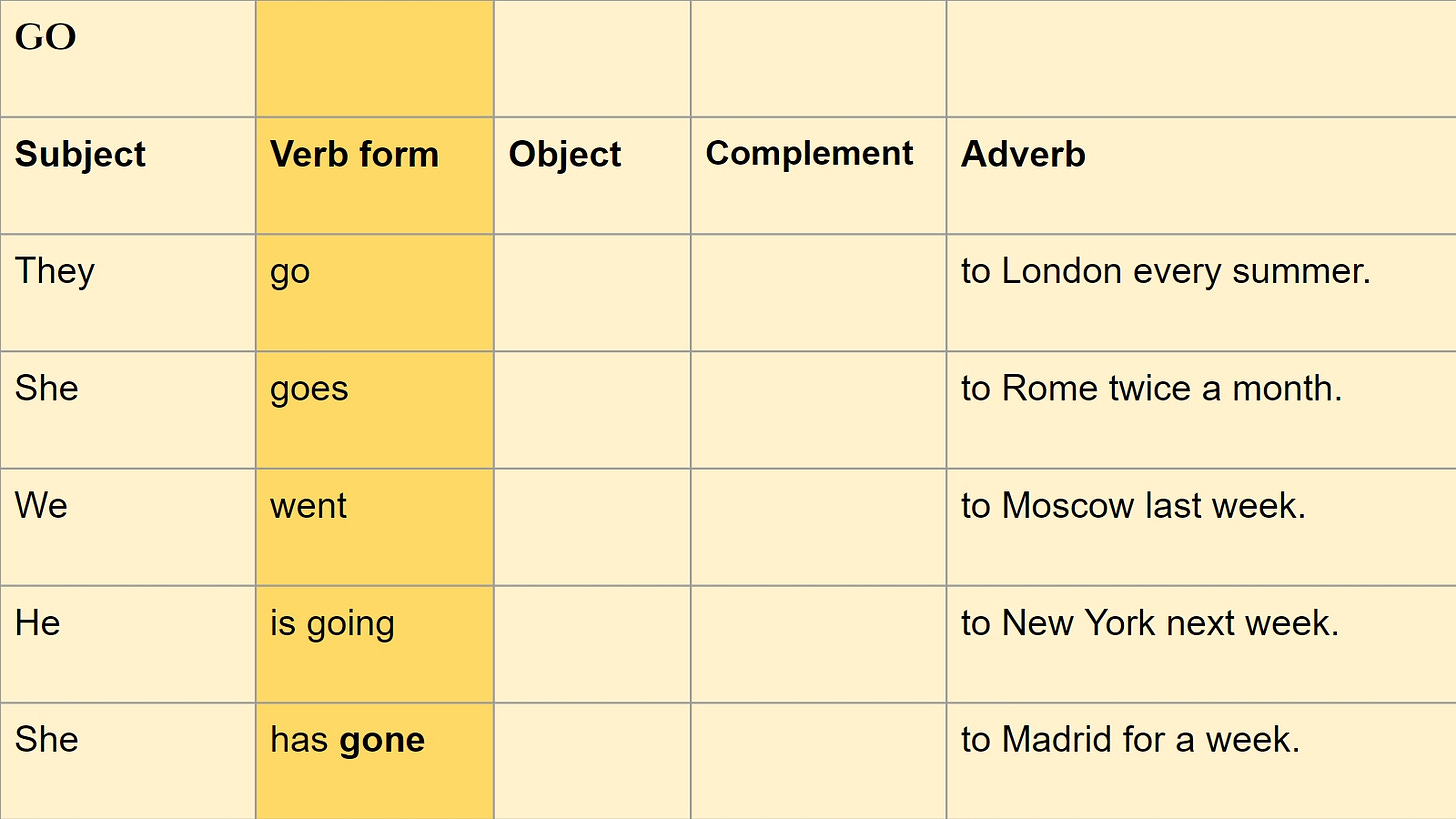

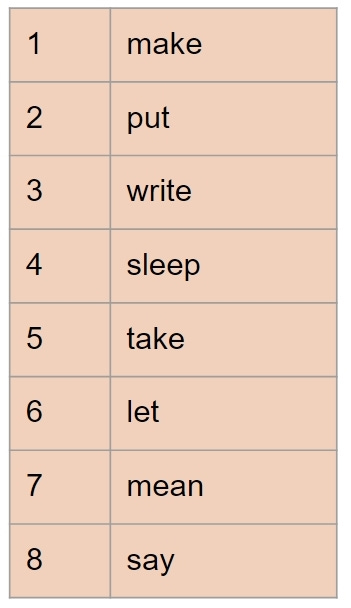

There are five possible forms for every English verb. We can present a chart like the one below to help students create useful sentences.

The following is an example of the chart for the verb ‘to fly’. I have included a blank chart at the end of the discussion for you to photocopy.

FIGURE 1

I have used European geography because my students are from Europe. Change the examples so they are relevant to your students.

Notice the column headings I’ve used (subject-verb-object-complement-adverb). We need to be brief when constructing example sentences (remember the overly detailed map?), but mustn’t exclude any essentials (remember the zoomed-in landmark-less map?)

Grammar and semantics are paired in language; neither walks alone. Example sentences should reflect that fact. By including the headings 'object-complement-adverbial’, we can both give the teacher leeway in sentence construction and offer important information for the learner (word order), even if it’s only passively noticed. Word order is not the focus here, but in any sentence-building exercise, you should at minimum passively expose the learners to it. Word order is an English essential.

“She flew” is useless as an example sentence. There are no essential details that show a learner the verb is in the simple past form. It also doesn’t show what other basic elements usually go with it, like an adverbial of place.

But equally useless for our focus, is an example sentence like, “My great Aunt Sally, who I haven’t seen for years, is flying to Moscow, my favourite city, with my cousin, next week, which happens to be…”

You get the idea. Stick to the basic features of English, but don’t exclude the essentials.

“She flew to Moscow last week”.

This puts the verb in context. It shows that we usually fly to a place and the time adverbial tells us it is the past. Equally important, is that the sentence above is something a native speaker is apt to say.

Look again at Figure 1. Notice that I have highlighted the verb form column. That column is in fact your irregular verb list. Do you need to do this for every single irregular verb? No, of course not. The students do!

Let’s see how we can get them to do just that.

Pre-teaching warning: You will be using this chart a lot, probably more than 20 times for a week or so. Students can replicate the chart in their notebooks but should be aware that they’ll be writing five example sentences for many verbs. (I usually insist that they replicate the chart in their notebooks for the first twenty verbs. They might do better with a two-page spread. After that, I figure their brains will have absorbed the structures. They can then simply write five example sentences as one normally would in a notebook for subsequent verbs. However, I have found that most students continue to use the word order template throughout their notebooks. It gives them a sense of security.)

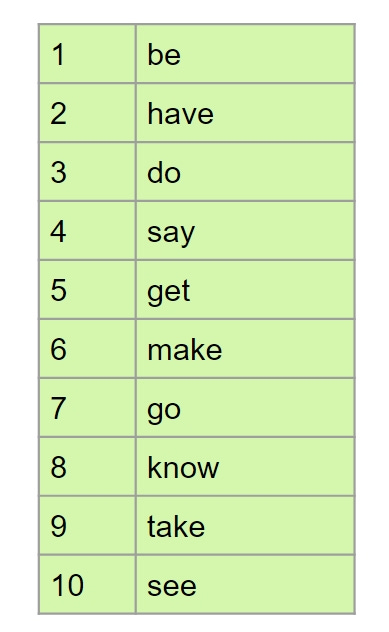

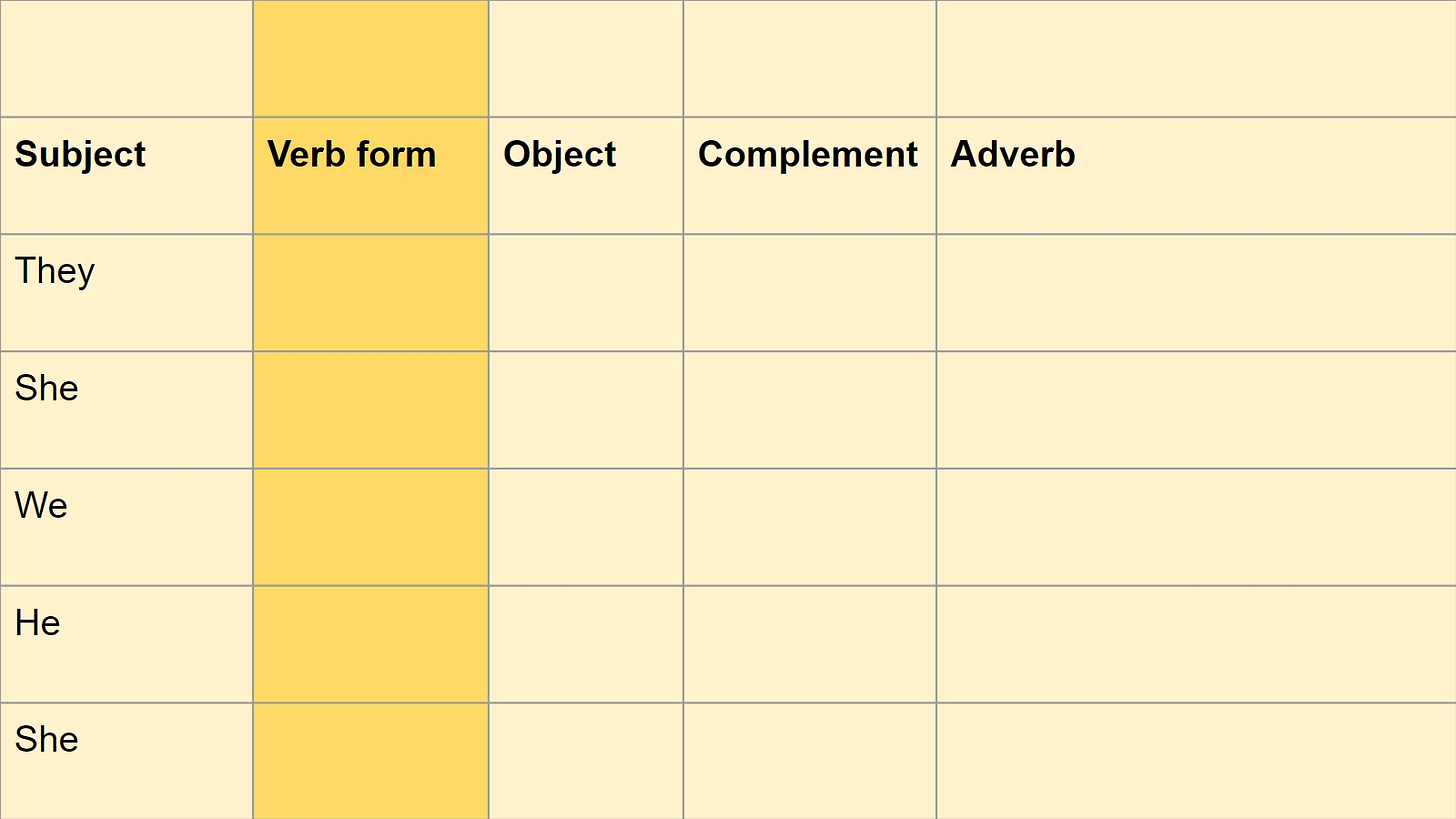

Ask students to guess the most frequently used verbs in English. Write their answers on the board. After their responses have fizzled out, write the following list on the board.

Tell the students that these are the ten most frequently used verbs in English. (Depending on your students’ country/ies of origin, you might prepare a list before the class of their language’s ten most frequently used verbs. The similarities might be surprising and enlightening to them. That insight will come in handy in subsequent lessons.)

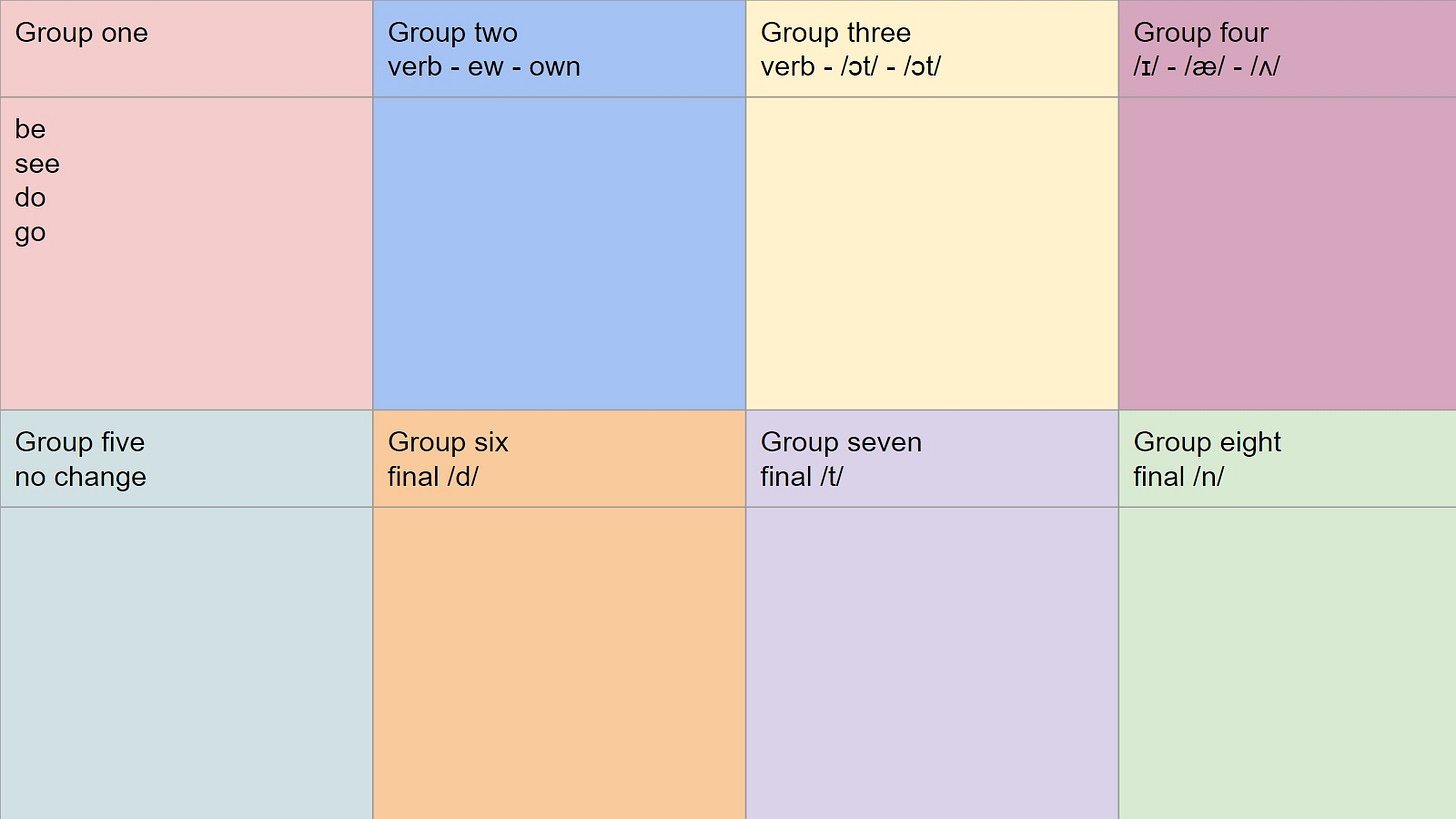

Now, hand out two sheets of paper. One is the infamous irregular verb list (find one that has around 150 verbs), and the other is a photocopy of the image below. (Do your best to produce photocopies with colour). This will be referred to as Figure 2 throughout the remainder of this discussion.

FIGURE TWO

(If you have a student who is colour-blind, work out some other way to mark the boxes with her or him.)

Point out that the first box, titled group one, is complete. Refer them back to the five forms exercise, which should now be drawn into their notebooks (Figure 1), and show them example sentences for to be and to see. Explain that to be is a special verb and you’ll explain it in more detail in another lesson. For now, they should simply notice the similarities between been and seen. Tell them this is a language pattern.

I hope you are noticing that I don't have to do much to change the example sentences. By making them this easy, the students should be able to make example sentences themselves without many mistakes.

Students should copy your example sentences into their prepared notebooks.

Next show them example sentences for to do and to go. Again point out the similarities between the past participles done and gone. (You might want to tell them that 400 years ago these forms rhymed.)

Any questions about unrelated grammar issues or any other unrelated language issues, ( is ‘being’ very common? when do we not use continuous? when do we say has been to X vs. has gone to x, etc.) should be put aside for now. It’s important to try to keep yourself and the students focused on the task at hand—acquiring irregular verb forms—rather than vectoring off into space. Verbs by their very nature invite vectoring! Gently assure the students that you will come back to these important questions another time. For now, we are just focusing on irregular verb forms.

Now refer students to their irregular verb list. Have them cross off the verbs that you have looked at (be, see, do and go) and have them copy your example sentences for to do and to go into their notebooks. (They will have plenty of opportunities to create their own sentences later. For now, it’s important to keep the ball rolling.)

Go to figure 2. Remind them that box number one is complete.

Now we’ll go to group two. Tell the students that the irregular forms in this group have simple past forms that rhyme with /ew/ and past participle forms that rhyme with /own/. (Resist the temptation to re-write the irregular verb list here! Just write the base form of the verb in the appropriate box. The rest of the forms will be recorded in figure one in their notebooks.). Have them look through their irregular verb list and find the verbs that follow that pattern.

Elicit their findings and write them on the board. Point out that the past participle of the verb to draw, drawn, is an anomaly, but still belongs in this group.

Have the students write the verbs for group two into the appropriate box of their colour-coded chart (figure two).

blow, draw, fly, grow, know, throw

Tell them to cross these verbs off their irregular verb list.

If your irregular verb list has the verbs mow, sew and show, have the students make a line under the last verb from above (on my list that’s throw). You can explain the forms of these semi-irregular verbs in more detail when you create example sentences. Your chart could now look like this:

Continue with the five example sentence exercise, figure one, for the six verbs in group two (exclude mow, sew and show for today).

You can practice these verbs with the students any way you like, reading aloud in paired tasks, making questions, and then answering, etc. I often do a quick speaking practice I call The Big Brag. (I’ll include the activity at the end of this discussion.)

I suggest taking a break from this exercise at this point and moving on to other material after working on each of the different groups in figure two. I usually work on one group a day at the beginning of the class.

The next two groups, groups three and four have a similar number of verbs as groups one and two and can be practiced the same way as you practiced groups one and two. Don’t forget to have students cross off the verbs from their irregular verb list every time you finish a group. When all the work for groups one through four is done, you can tell the students that tier one (the top half of the chart), is complete. Except for some very obscure verbs, there are no other English verbs that have these patterns.

Here’s what figure two looks like when the first tier is complete. The verbs with an asterisk have anomalies in spelling.

Notice that some verbs are not very frequently used. You might want to eliminate some of them. If you’ve read my post on Vocabulary Frequency you’ll know that high-frequency vocabulary items are essential for students while low-frequency words are best reserved for topics that require them. If a verb is on the C1 frequency list, it’s obviously not useful for beginners and might not be very useful for advanced learners either. This exercise is to help them to predict and acquire irregular forms not to learn C1 vocabulary.

Here are the verbs from groups one through four in their frequency categories.

Personally, I only teach A1, A2, and B1 when exposing students to irregular forms. They’ll acquire the other verbs as they need them.

A side note about the pronunciation of group three verbs. That ‘ought’ is pretty daunting but the ‘aught’ of catch and teach throws most students into a tizzy. The range of bizarre pronunciations I have heard for these verbs is unfathomable. Leave it for now. If you sense that it’s going to be an issue, you can come back to this group in the future and do a pronunciation exercise with these verbs. For now, you can just tell them that all the past and past participle forms in this group rhyme with ‘not’ and leave it at that.

In the second tier of figure two (groups five through eight), there are many more verbs per group and the task needs to be approached slightly differently.

Groups five through eight have around eighty useful verbs, that’s approximately twenty verbs for each group.

Let me take a minute to explain why I have arranged the groups in figure two as I have. By presenting the groups this way, the possibility of putting a verb in the wrong group is eliminated. Groups one through four are quite distinct and have now been crossed off. If you look ahead to group eight (ends with /n/), you can imagine the confusion if group two items (flown, grown, etc.) hadn’t been crossed off yet. This order reduces confusion by eliminating confusing elements first. Also, each group in the second tier has at least double the items as the groups in the first tier. Group eight is last because it has the most variation. They all end in /n/ but the internal elements are quite varied.

The order ensures that subsequent verbs will not be placed in the wrong box, with one exception. The verb to read. It is not in group five (no change) as many incorrectly assume. If we point out that all the verbs in group five end with a /t/, the students will realize that ‘to read’ cannot be in group five. Tell them that although the spelling doesn’t change, the pronunciation does. This verb needs to be in group six (ends in /d/).

For the remaining groups, on tier two, I write the following eight verbs on the board and ask the students to predict which groups they fall into.

I correct them if they’re wrong, but honestly, I can’t remember the last time I had to correct anyone, (except now and then after introducing ‘to read’.) This shows students that they do in fact know this stuff! They just can’t do it in list form, because the brain doesn’t work that way. It would be amiss to not point some of this out to them. Most language learners find it interesting to discover how the mind works and every language student needs a boost in their confidence. They will see that ‘format’ (often called mental framing), is incredibly important to language learning.

Next, make sure you have them cross off the eight verbs from their irregular verb list and start to make example sentences for figure one in their notebooks.

The rest of this should be pretty simple now.

The colour-chart, figure two should now look like this:

Have them choose five verbs from their irregular verb list for each of the last four groups all the while crossing off the verbs as they go. Every day have a short session (ten minutes max.) where they can write five example sentences for one group at a time ( they can do this together, in pairs, or however you think is best), while you walk about monitoring. Do this as a daily warm-up until every verb has been crossed off the irregular verb list. You might not want to spend too much class time on the example sentences, but get them to do the five example sentences for at least two verbs from each group for four days. That's only ten sentences a day and shouldn’t take them too long. It’s important that you monitor some of their examples to keep them on track. Encourage group work to reduce your load. Depending on the class you could always assign some example sentences for homework.

The final and really important event is to shred their irregular verb lists. Make a big show of this. Stand on a chair, whatever, and make it like a celebration. Hold your irregular verb list over your head and make a speech, “I condemn thee to the infernal fires of the wastebasket, never to tarnish my notebook again. I am done with you oh infernal list”, and then energetically rip the list into bits and throw it into the air. Encourage students to join in the fun. Have a royal wastebasket bearer carry the bin around as students create and toss confetti. I usually bring biscuits and coffee for this celebration! (The eventual clean-up proves an excellent opportunity for spontaneous chit-chat)

And that’s that. If you review this often, choosing one verb from each group every few days, your students will have these verbs done and dusted without stuttering, “I’ve fly-flew-flown to Moscow twice” ever again!

You can now start to explore much more interesting concepts with verbs without having to always stop halfway through to correct the forms of any given verb and the students with their newly gained confidence in this area won’t fall prey to the speaking block when they realize mid-sentence that they don’t know some particular verb form.

And that’s definitely cause for celebration.

Extras

The Big Brag - a speaking activity

This is a speaking exercise I do to reinforce the material.

Students sit in groups of three with a stack of irregular verb cards on the table face down. If you're pressed for time, have the students make the cards before time. Use at least five verbs from each of the eight groups.

Place the cards face down in the middle of the table.

Std A picks up the first card and reads the verb to herself. (The card will have the five forms on it) Std A does not show the card to the others (unless of course the students really need the crutch).

Std A makes a sentence with the verb shown on the card in the present tense and uses ‘I’ as the subject.

Std B must make a sentence with the same verb, keeping the theme of std A’s sentence, in the simple past.

Std C must make a sentence with the same verb, and same theme, in the present perfect.

It might go something like this:

A: I draw pictures every day.

B: I drew a picture yesterday.

C: Hmph! You think that’s something! Well, I have already drawn 5 pictures today!

You might want to write a template for std C’s response on the board so the students can accurately do the big brag of std C.

Hmph! You think that’s something” Well, I have already ___ 5 ___ today!

Model the bragging tone. It adds some spice to the exercise.

Student B then picks up a card and the students rotate turns and tenses accordingly.

Do this for a few rounds every day. I often have a table set up in the corner for students to play when they have finished some other task before the others. I call it the Bragging Station.

Blanks for Photocopies

Figure One

Figure Two

Excellent as always!! Happy new year!!